Golf’s Movers and Shapers – Architects are Staying Busy with Renovations

Through the early 2000s, golf architects experienced a building boom unlike anything in the history of the sport.

Although the building of new courses has slowed in recent years, golf course architects remain extraordinarily busy.

And while having the opportunity to stretch their creative muscles on an untouched piece of land remains the preeminent task for architects, the opportunity to massage existing layouts and put a fresh spin on a course via renovations now defines the livelihood of some of the best movers and shapers in the country.

Jeff Mingay, a Canadian who helped create Cabot Links in Inverness, Nova Scotia on Canada’s east coast, now does almost all of his work in the U.S. He says this year was ‘busier by far’ than a year ago, working construction jobs at clubs through the Pacific Northwest and into middle America.

“The cool thing about the work is that every project is different,” says Mingay, who works with six clubs in the Seattle area and two in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area.

Architect Jeff Mingay started his own design firm in 2008 after working alongside Rod Whitman.

With the U.S. being the best‑supplied golf market in the world – boasting almost 45 percent of global facilities – architects are still in demand to keep courses as technically and environmentally advanced as possible, and that’s especially true as it relates to water usage.

Renovation projects have by far replaced new construction as the largest source of U.S. golf course development activity. After the building boom between 1986 and 2005 saw almost 5,000 new 18‑hole courses open, there have been 492 new courses built since. Over the past decade, there have been approximately 1,000 major course renovations completed that represent a total investment of at least $3 billion. And there are also thousands of other minor reshaping and remodeling projects to keep architects busy.

Florida leads the way in renovations over the past five years, with 10 percent of its courses undertaking major projects (Texas, California, North Carolina, and South Carolina round out the top five).

Jan Bel Jan is an architect based out of Jupiter, Florida, and began her career with Tom Fazio. After winning numerous awards for her work, she formed her own golf design firm in 2009 and has been instrumental in designing ‘ScoringTees,’ which provide an alternative ‘course within a course’ for many clubs in Florida and beyond.

“These tees are gender neutral, age neutral, skill neutral, and they help good players with three things: course management, short‑game improvement, and learning how to go low,” Bel Jan explains.

A certified arborist, Bel Jan says that although clubs are now interested in these new tees to make for shorter, player‑friendly layouts, many of her renovations start with water.

Jan Bel Jan at one of her Florida course projects.

“When you reduce the amount of water, you’re also reducing the other inputs that may be flowing – less fuel and maintenance, plus labor. In this market (Florida) and in most every market, labor is a big deal. Where do you find people who want to work and are skilled at it?” she says.

“People think with all the rain (in Florida) there is no problem, but there is,” she adds. “All water is managed in the state of Florida and there are a lot of things measured – what you can and can’t use. Applying water exactly where it needs to go is really key.”

While it’s recently become en vogue to be ‘environmentally friendly,’ architect Greg Martin of Chicago has been preaching environmental improvements at golf courses for a number of years. This “refocusing” is what Martin now knows, as clubs look to make their courses more efficient with natural resources, an approach that also eventually saves money.

“Most of my work is based upon how to allocate resources more directly to the playable surfaces,” says Martin, who works with a handful of municipal facilities in the Chicago area, as well as many clubs in the Midwestern U.S.

“You’ll take certain areas out of play and refocus resources and say you’ve got 150 acres of wall‑to‑wall green, now you can remove 40-50 acres and make them out‑of‑play, native, or wild areas.”

“A lot of the work that I’ve been doing with municipalities is to provide a roadmap to redevelop their golf courses to be more sustainable economically,” Martin adds. “Municipalities and/or park districts are all looking for a way to manage their resources and this is a good way to do it.”

Of the more than 400 course renovations done in the last five years, 55 percent involved daily fee or municipal facilities.

Martin says he’s always appreciated the opportunity to make a golf course more sustainable and now it’s turned into the kind of project that keeps him busy.

“I’ve always been excited for how golf can provide a wider community benefit,” he says. “What’s interesting is that during the golf boom no one wanted to talk about environmental benefit, they wanted to talk about building $20 million cool things.”

Ian Andrew works with 15 clubs in the U.S. and has ‘steady work.’ The sheer quantity of courses he works with helps to keep him busy and a lot of the clubs will be asking for master plans, which means Andrew will be researching many aspects of a course.

“When you do very large projects, the work comes and it goes. The way somebody like me survives is the volume,” he explains. “There is always a big job sitting out there somewhere, but there are smaller jobs all the time. If you’ve got 50 clubs, you’ve got 20 that are very active and 30 that are random. When you’ve got enough clients, you know something is eventually going to come.”

Architect Ian Andrew lays out a bunker rebuild plan in the sand at Knollwood CC in New York.

Having an opportunity to build something from scratch is still the ultimate for many architects.

The NGF has been tracking almost 40 new 18‑hole facilities currently under construction and close to 60 in the planning stages in the U.S. alone.

“I don’t think there are very many architects who tell you they wouldn’t want something new,” Andrew says. “Something new is self‑expression. It allows you to share your feelings for how you think architecture should be and what it should feel like and what players should feel like,” he says. “There is an enjoyment in that.”

Andrew says it’s not a struggling time for architects, as people who can design and build their own work will be valuable assets to courses moving forward.

“A lot of younger architects ask how to make a go of it if you’re not going to be building anything new,” Andrew adds. “You may re‑build a series of greens, or two or three courses worth of bunkers, and it’s actually a lot of work over time. If you’re doing grass work and tree work and everything else, it’s amazing how much work there is.”

Bel Jan says it’s not surprising to see architects hard at work at making changes to the courses that were built during the boom, as design ideologies change after a few decades.

“People want to have a fresh look, hardly any different than what we would do in our houses,” she explains. “Part of it has to do with technology, but these golf courses are 20 to 30 years old. There have been upgrades in between.”

Short Game.

"*" indicates required fields

How can we help?

NGF Membership Concierge

"Moe"

Learn From NGF Members

Ship Sticks Secrets to a Hassle-Free Buddies Golf Trip

Ship Sticks Secrets to a Hassle-Free Buddies Golf Trip

Whether you’re the head planner of your upcoming buddies golf trip or simply along for the ride, we’ve gathered a few easy ways to keep everyone in your group happy.

Read More... Golf Course Turf, Soil and Water Quality Diagnostic Testing

Golf Course Turf, Soil and Water Quality Diagnostic Testing

As humans, we see our primary care physician on a regular basis to proactively evaluate our vital signs. Likewise, a superintendent should perform frequent diagnostic testing on their golf course.

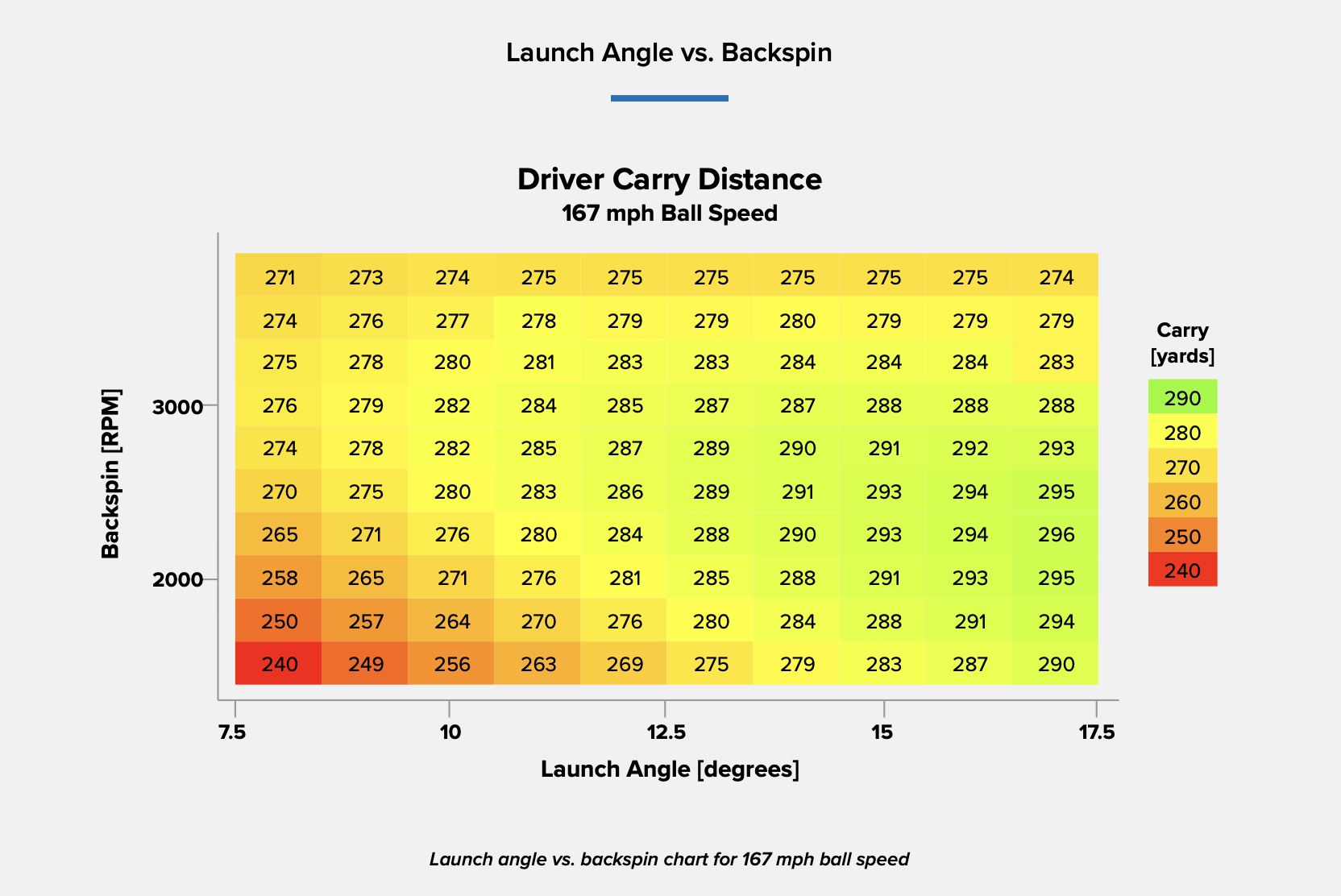

Read More... Unlocking Distance: Launch Conditions and Angle of Attack

Unlocking Distance: Launch Conditions and Angle of Attack

We’ve long known that higher launch and lower spin is a powerful combination for generating consistently long and straight tee shots. A key factor in optimizing launch conditions, one often overlooked, is ...

Read More...