One Hole at a Time

In 2013, his first year as president of the PGA of America, Ted Bishop attempted to tackle one of the biggest obstacles affecting participation: the time it takes to play. He purchased time clocks and planned to install a pay-by-the-minute system at The Legends Golf Club, the course he owns and operates in Franklin, Indiana.

“I had this vision that we were going to say that it should take 2 hours and 10 minutes to play an acceptable nine holes and you could come punch in and punch out and your credit card would be charged by the minute,” Bishop recalls. “If you only had an hour to play then you’d be charged accordingly. I thought the concept was brilliant.”

Bishop even got the buy-in of the PGA and found five other Midwest courses to partake in a test-pilot program. He expected it to attract customers late in the day, especially from businessmen hoping to squeeze in a few holes before sunset.

“We had a few conference calls, everyone was fired up and put the time clocks in and nobody, including myself, could figure out the right way to market it. It fell flat on its face,” Bishop says. “Like a lot of things I’ve done in my life, it sounded great when I did it, but didn’t always work out that way.”

But the concept still has its supporters and a number of companies have introduced systems that allow golfers to pay by the hole – essentially paying only for as many holes as they play. For golfers, it’s a way to tee it up before or after work or whenever they might have a window. For facilities, it’s a chance to boost incremental revenue on what is typically unused inventory. On paper, it should be a viable alternative for both golfers and golf courses. But are these “solutions” proving to be any more successful than Bishop’s effort?

NGF research finds that less than 1 percent of golfers have used a pay-as-you-go approach for golf, yet 46 percent of core golfers (those who play eight or more rounds a year) say they’re at least “somewhat interested” in such an offering. Rounds of golf other than nine or 18 holes aren’t particularly common, but may grow as savvy operators seek solutions to maximize yield management and mitigate oft-cited barriers to traditional participation related to time and money.

Golf By The Hole

Harvey Silverman, co-founder of Quick.Golf, and Pascal Stolz, CEO of eGull Pay, are leading the charge to make partial-round golf part of the game’s vernacular.

Silverman launched Quick.Golf, a browser-based service that allows courses to sell golf by the hole, in September 2016 and says users are playing anywhere from three to 13 holes, with six being the average number. Course operators can choose from a revenue share or a subscription model designed for municipal facilities that aren’t set up to pay third-party commissions. So far, it doesn’t integrate with any tee sheet or point-of-sales system. Quick.golf has signed up 48 courses and predicts that number to grow to between 100 to 200 by the end of 2019. “The magic number in golf technology is once you get to 500, you’re for real,” Silverman says. “It’s going to take us a while to get there.”

Stolz cited a similar number of U.S. courses, along with 70 in Europe and Australia. (eGull is owned by Blue Green, France’s largest course owner/operator.)

eGull is among those companies trying to create a niche for pay-per-hole golf.

If the “time barrier” is as significant as suggested, why haven’t these upstarts done better?

One possible answer is that the golf industry is notoriously slow to adopt change. Even modern-day standards like metal woods and soft spikes weren’t immediately accepted. Stolz observed that many courses still don’t offer nine-hole rates despite the fact that more than 3 million nine-hole rounds were recorded by GHIN in 2018, according to the USGA, and nearly two out of three golfers report playing at least one nine-hole round last year.

Silverman blames the slow growth on course operators and PGA professionals unwilling to think outside the box when it comes to offering an alternative way to play.

“We’re constantly pushing this rock up a hill against a mindset that says golf is either nine holes or 18 or that’s it,” Silverman says.

Stolz cited a “fear factor” as a leading deterrent.

“Golf is the only sport that you can’t play for an hour,” Stolz says. “For some reason, the golf industry doesn’t want to give away a nine or 18-hole potential round for an I-don’t-know-how-many-holes-you’re-going-to-play.”

NGF research shows that younger golfers — those between 18 and 49 — and core golfers who play less frequently are almost twice as interested in a pay-per-hole option than their older and more avid counterparts. If such a system was utilized by their home course or one nearby, 10 percent of those interested say they would “definitely” play more. Another 30 percent indicated they would “probably” play more often.

A Win-Win Deal

Among operators, some have expressed concern that the pay-per-hole systems might have problems interacting with their existing management and tee-time booking technology. Others have said they’re worried about how these limited rounds might interfere with or negatively impact regular play.

Allan Parkes, the golf operations manager at Shepherd’s Crook Golf Course, the Zion Park District owned and operated layout in Zion, Illinois, isn’t among the detractors. He added Quick.Golf last year and called it a win-win deal that saves money for customers while generating revenue at off-peak times.

“I couldn’t find a reason not to do it,” Parkes says. “We have unused inventory that we’re throwing in the garbage every day. The way I look at it is, can I get some share of a golfer’s wallet instead of none of it?”

Parkes recounted how a half-dozen workers at a distribution warehouse for the Meijer Grocery chain in nearby, Kenosha, Wisconsin, drive 15 minutes across the border, play for 30-35 minutes and step on the gas to get back to work before their hour-long “lunch break” expires.

Both Stolz and Silverman agree that early adopters who believe in the concept are finding success with their products, but it requires a commitment. Stolz says 60 percent of golfers who try eGull use it again. The average user is playing seven holes and becoming a recurring golfer.

“We’re finding that customers who were playing three times a year are instead playing twice a month,” Stolz says.

eGull’s mobile app works much like Uber, tracking in real time how many holes a golfer plays via a smart phone’s GPS and bills the golfer only for the holes played. It is free for courses to join eGull, which debuted in France in April 2017 and the U.S. seven months later, and employs a revenue-share model charging a 20 percent commission. It is also exploring a subscription plus commission-based model in 2019. Stolz said the company projects to be in 1,500 courses by the end of 2020, and said part of its strategy is to identify pockets of interest of 15-20 courses in metropolitan areas to stimulate expansion.

“For it to take off, some of the big tee sheet providers — EZLinks or GolfNow — will have to open up their gates so we can indicate tee times for golfers that want to play just a few holes,” Stolz says.

He says 80 percent of tee times using eGull are teeing off after 2 p.m., when golf courses tend to be less crowded.

Parkes mused that golf course operators could learn a thing or two from the restaurant business and how they manage their inventory.

“There is no waste,” Parkes says. “It all goes in to the vat and tomorrow’s potato leek soup special. The people who do the best at managing their inventory are going to have the best bottom line and I’m all for anything that can help generate more play.”

The question is whether a pay-per-hole offering, whether done internally, through a tee-time management system or by an outside company like eGull or Quick.Golf, might be viable for particular facilities from a logistical and execution standpoint — not to mention consideration of whether a course’s routing is conducive to it. The interest seems to be there, but ultimately operators have to determine whether it will work for them.

Short Game.

"*" indicates required fields

How can we help?

NGF Membership Concierge

"Moe"

Learn From NGF Members

Ship Sticks Secrets to a Hassle-Free Buddies Golf Trip

Ship Sticks Secrets to a Hassle-Free Buddies Golf Trip

Whether you’re the head planner of your upcoming buddies golf trip or simply along for the ride, we’ve gathered a few easy ways to keep everyone in your group happy.

Read More... Golf Course Turf, Soil and Water Quality Diagnostic Testing

Golf Course Turf, Soil and Water Quality Diagnostic Testing

As humans, we see our primary care physician on a regular basis to proactively evaluate our vital signs. Likewise, a superintendent should perform frequent diagnostic testing on their golf course.

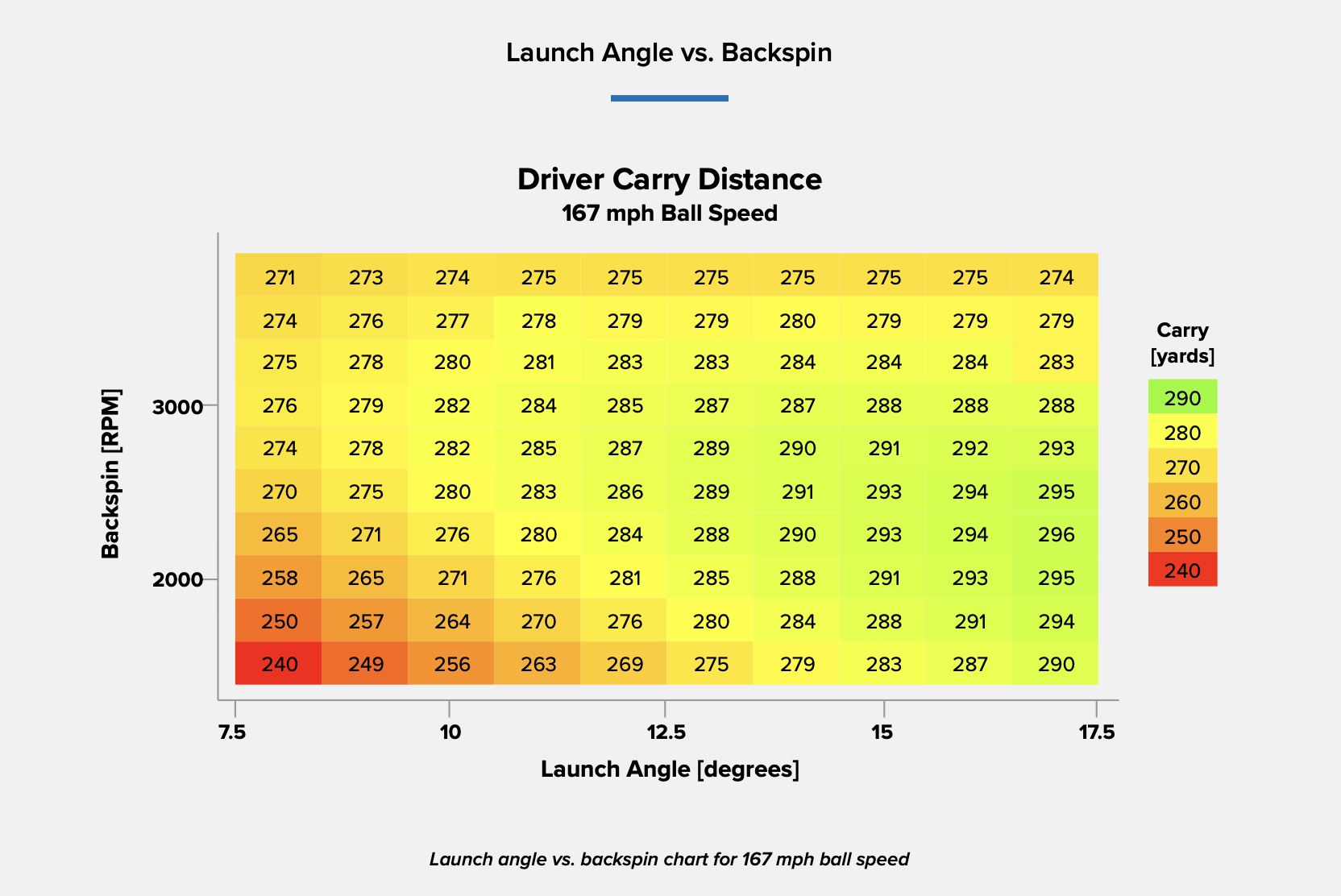

Read More... Unlocking Distance: Launch Conditions and Angle of Attack

Unlocking Distance: Launch Conditions and Angle of Attack

We’ve long known that higher launch and lower spin is a powerful combination for generating consistently long and straight tee shots. A key factor in optimizing launch conditions, one often overlooked, is ...

Read More...