Welcome Newbie!

By Trent Bouts

(This article originally appeared in the March issue of Golf Business, the official publication of the National Golf Course Owners Association, and has been reprinted with the approval of the NGCOA)

The late Steve Jobs did pretty well introducing products the masses weren’t yet clamoring for. “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” he once said. If Jobs was to be believed, Apple never did a scrap of market research preparing game changers like the Macintosh, the iPod and the iPhone. The company simply built them, and people came.

Golf is still waiting on a Steve Jobs, someone whose innovation transforms the marketplace, unleashing that wave of latent interest in the game that course owners have heard and read about for so long. Simply building more courses in the 2000s, believing golfers would materialize, didn’t work. That represented more of the same at a time when consumers were becoming anything but.

The entrance to a public golf facility in Florida, which has more golf courses than any other state in the U.S.

In part thanks to Jobs’ own work, Millenials and, yes, many of their parents were finding new ways to occupy their time, ways that psychologists say shortened their attention spans and stimulated an appetite for instant gratification. Hardly things golf has ever been famous for.

Jobs launched the iPhone early in 2007. Later that same year, after surveying more than 2,000 golfers and with far less pomp and ceremony, the National Golf Foundation made an announcement of its own. As the world was exercising its thumbs like never before, NGF president and CEO Joe Beditz dared wonder if the NGF’s own Golf Consumer Profile wasn’t itself a game-changer.

The NGF survey found that a “high percentage” of golfers, including even those “hooked” on the game, were at times either “intimidated or embarrassed” at golf courses. The percentage went up among women, and infrequent golfers were “much more” likely to feel that way. Blamed for what the NGF characterized as these “bad feelings” were the general environment at the facility, its staff and other players.

It seemed like an a-ha moment.

As Beditz wrote then: “Until golf course operators focus on the basics of intimidation and embarrassment, it’s unlikely we’ll see anything more than nominal growth in golfers and rounds. If I were an operator, I’d view these issues not as a fact of life, but as an opportunity. An opportunity to differentiate myself in my market and grow my business, by being the facility where everyone feels at home. That might just be the key to player development.”

In the decade since, golf has bent over backward introducing new players to the game—by some measures, as many as 12 million people gave it a try over that period. Yet the number of actual golfers, the people who keep facilities in business, has dropped by three to four million. Those numbers should be shocking for anyone in the business, but New York-based consumer behavior psychologist Peter Murray doesn’t find them surprising.

Murray is not a golfer. He dabbled in his youth, but quickly found the game too difficult, a common cry among newcomers. Place that difficult endeavor in an intimidating environment, he says, and small wonder so few people stick with it. “Really, it has nothing to do with golf and everything to do with our own perception of ourselves, our self-identity,” he says. “We absolutely avoid things we don’t perceive we can be good at.”

Ultimately, the main driver in consumer decision-making, Murray says, is emotional. We need to perceive a benefit, and while that benefit might be physical, it’s how we feel about it and how it makes us feel about ourselves that determines our purchase or, in golf’s case, our participation.

“Self-efficacy—our belief in our ability to succeed—plays a very large role in what we will attempt and what we will continue to pursue once we’ve attempted something,” Murray continues. “If you can’t perceive how you will feel good by doing something, then you won’t do it.”

Golf course operators need to focus on lessening intimidation and embarrassment for beginning golfers.

Recently, Golf Business invited a handful of newcomers to the game to visit golf facilities and report back on what the experience was like. It was hardly rigorous science, but it offered an anecdotal snapshot of whether the game and its environs were any less daunting to newbies these days. The results were far from encouraging.

The newcomers concerns emerged immediately after driving through the front gate. Am I allowed to park anywhere? What’s a bag drop? Do I carry my bag inside or do I have to pay first? Which door do I go in? Even, Which building do I go in?

And once inside, Who do I pay? To some, the pro shop meant a place to buy equipment, as it is in most bowling alleys. They were looking for a counter and a cash register as soon as they walked inside and when they didn’t see one, it only heightened their concern that they had entered through the wrong door.

Then, “How can I tell who works here?” One mistook a fellow golfer for a staff member because the golfer was wearing a shirt with the course’s logo. All expressed concern that no one approached them offering help.

Not surprisingly, every one of our handful of guinea pigs reported feeling uncomfortable to some degree, and sometimes in multiple instances.

Not one of our test subjects felt good about it, and no one had even attempted a backswing yet.

“To get people to do something new is difficult, even when they are not intimidated by it,” Murray explains. “We’re creatures of habit. So, to get someone to do something new that requires a knowledge level or skill level that we don’t have is asking a lot. And the knowledge and skill required to play golf is extraordinarily high. Whereas you don’t need to be Roger Federer to walk onto a tennis court and have fun.”

None of the above would surprise Beditz. “Our onboarding system for new golfers is a bit too unrefined,” he says. “At a golf course, the number of first timers is small but incredibly significant, yet so easy to overlook. All of our energies are focused on the people who show up every week, which is only natural.”

Indeed, it may be natural. Golf course operators need those regular consumers and keeping them happy produces a better ROI than chasing newcomers, at least in the near-term. But that focus on the bird in the hand might also be a consequence of an alternative culprit—tradition.

“There’s learned behaviors here that have to change,” Beditz concedes. “And we are really working hard and thinking about what is stopping this change from occurring, and what can we do to modify that. We’re not blaming the operators. We’re trying to work out why certain changes aren’t being adopted on a grander scale.”

Newcomers to golf have many concerns: what’s a bag drop? Do I carry my bag inside or do I have to pay first? Which door or building do I go in? What tees do I play?

Beditz is quick to point out that some operators are enjoying considerable success with approaches that address issues of intimidation around the game. “But they are not as widespread as we would expect, where you think they would naturally catch fire, that success would beget success, that best practices would beget best practices and even better practices,” he notes. “We don’t see that happening so much and we’re very quizzical about that.”

From a psychological perspective, Murray believes that “re-engineering” golf to create a less intimidating environment and experience is eminently possible. Introducing design elements to the facility, helpful signage and a more welcoming atmosphere is, in his view, “easy, easy” stuff to do. But where you get the most leverage, he says, “is in the human contact, the golf pro or whoever you run into

when you go to play.”

That face-to-face interaction can overcome a lot of other shortcomings. “Just like in a therapy situation, people can do amazing things they never thought they could accomplish when they are in a supportive environment,” Murray says. “To have people less intimidated and throw caution to the wind and expose themselves to possibly feeling embarrassed by how they swing the club, that becomes minor if they are in a situation where they feel like they are being fully supported.

“But golf is very tradition-bound, and that is an obstacle to suddenly becoming a psychologically sensitive institution that treats the customer as king, as opposed to ‘allowing’ the customer to use their pristine facility.”

That golf, as an industry, has not performed extensive psychological research among players and potential players, puts it out of step with many other industries, Murray says. Knowledge gleaned from that research could inform action, steps that golf’s professional organizations—those of owners, club managers and pros—could use to frame training programs. “That’s a path that a lot of industries go through,” he points out. “And it has the potential to make a huge, huge difference.”

One industry that has benefited from listening to its customer base is higher education. Murray says that over the past 15 years, colleges, forced by financial imperatives, steered their way through a 180-degree turn from a “holier than thou, head in the clouds” mentality that dictated to students what they could learn.

“They re-engineered what a higher education institution was,” he says. “They realized they are in the business of providing students with what the students believe they need. They realized they were in a highly competitive business with customers, and that requires an entirely different attitude.”

For examples, the University of Wisconsin now offers a course in Elvish, the Language of Lord of the Rings; MIT offers Topics in Comparative Media: American Pro Wrestling; and Temple University offers study in UFOs in American Society.

Golf might never find its Steve Jobs, someone who builds a facility and an innovative philosophy for satisfying golfers, new and old, that is as different as the iPhone was to what once hung on the wall or sat on the counter of every American home. But it needs to get closer to what works. Some are looking at Topgolf, with its informal virtual golf experience with drinks and a lounge atmosphere, as a potential bridge.

But for many course operators, their needs can’t wait. And even if Topgolf does turn out to produce a source of new golfers, given each facility’s $25-million startup costs, course owners can’t expect that one will ever arrive in their neighborhoods. But from his standpoint, Beditz believes as much now as he did in 2007 that one far more affordable and accessible key has already been identified.

“Until we do a better job of embracing newcomers, and helping them to achieve comfort and competence—and helping them to create a golfi ng network, or bring them into a golfing network where friendships can develop—then we’ll have a very hard time taking advantage of the vast amount of latent demand that exists for the game today,” he says. “Ask yourself, ‘How many golf courses identify first-time customers when they come through that door?’ I think until we learn to identify first-time golfers, we can’t begin to make them feel welcome.”

Beditz cites the message of best-selling management consultant Peter Drucker, which at its essence is that the purpose of every business is not to provide a product, but to create a customer. “We have to do a better job of that,” Beditz says. “We have to actually go out and get people from the street, go out and grab them, bring them in, all the way in. We can’t just leave the door ajar.”

Especially when newcomers don’t always know which door to look for.

Short Game.

"*" indicates required fields

How can we help?

NGF Membership Concierge

"Moe"

Learn From NGF Members

Ship Sticks Secrets to a Hassle-Free Buddies Golf Trip

Ship Sticks Secrets to a Hassle-Free Buddies Golf Trip

Whether you’re the head planner of your upcoming buddies golf trip or simply along for the ride, we’ve gathered a few easy ways to keep everyone in your group happy.

Read More... Golf Course Turf, Soil and Water Quality Diagnostic Testing

Golf Course Turf, Soil and Water Quality Diagnostic Testing

As humans, we see our primary care physician on a regular basis to proactively evaluate our vital signs. Likewise, a superintendent should perform frequent diagnostic testing on their golf course.

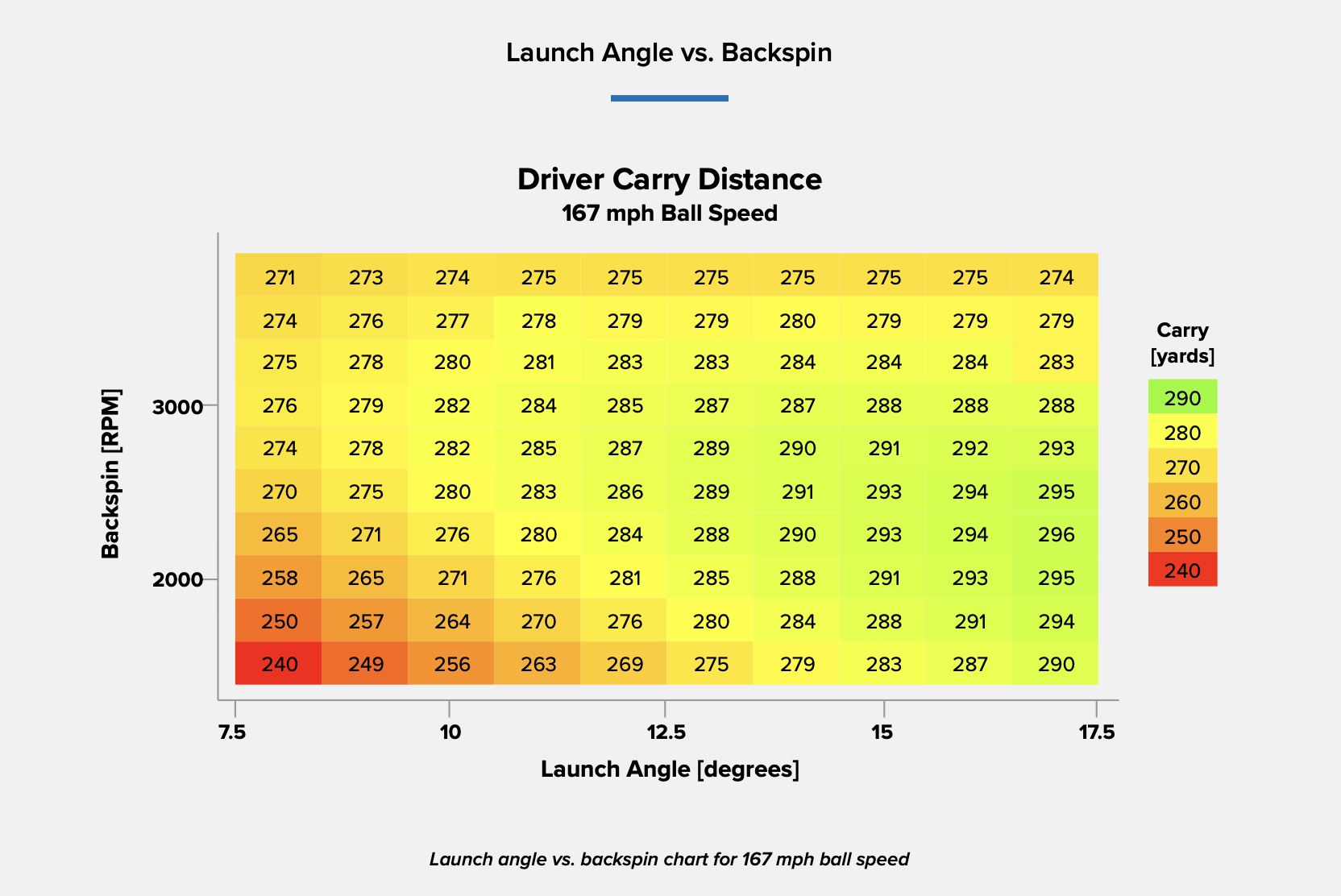

Read More... Unlocking Distance: Launch Conditions and Angle of Attack

Unlocking Distance: Launch Conditions and Angle of Attack

We’ve long known that higher launch and lower spin is a powerful combination for generating consistently long and straight tee shots. A key factor in optimizing launch conditions, one often overlooked, is ...

Read More...